How Common Is Nursing Home Abuse and Neglect?

How Common Is Nursing Home Abuse and Neglect?

Introduction

All nursing homes that receive Medicare funding (i.e., virtually all of them) explicitly agree and promise to help every resident “attain or maintain the highest practicable physical, mental and psychosocial well–being.” Yet, most of us have had a family member or other loved one who resided in a nursing home and suffered a far different experience. Far too many of us have heard achingly similar tales about the most vulnerable among us suffering abuse and neglect at the hands of the very people to whom their care was entrusted.

It has long been startlingly clear that the nursing home industry has failed, and is failing, to protect its residents from abuse and neglect. Elder mistreatment has a devastating impact on its victims, robbing them of dignity, quality of life and hope. For decades now, the industry has been plagued by reports of abuse and neglect — study after study reveals the extent and severity of this shameful problem. Nursing home abuse and neglect is also underreported, underestimated, and under-recognized. In other words, the problem is even worse than we think.

Most nursing home residents are vulnerable due to their decreased ability for self-care and chronic illnesses that limit their physical and cognitive functioning. Many are either unable to report abuse and neglect, or are fearful that such reporting will lead to retaliation, especially if they’re dependent on — and at the mercy of — nursing facility staff for virtually every aspect of their daily existence: bedding, food, medical treatments, hygiene needs, and mobility. In fact, research suggests that the 2.5 million residents in long-term nursing care facilities, which are presumably staffed by health care professionals, are at much higher risk for abuse and neglect than older adults who live at home (Hawkes, 2003).

Who’s At Risk For Nursing Home Abuse and Neglect?

By the end of 2014, just over 1.4 million residents were living in nursing homes in the U.S. Nearly two-thirds (65.6%) are women (CMS Annual Nursing Home Data Compendium, 2015). Around 1 million live in residential care facilities, variously referred to as personal care homes, adult congregate living facilities, domiciliary care homes, adult care homes, homes for the aged, and assisted living facilities (Hawkes et al, 2003).

National Mortality Followback Survey researchers estimate that more than two-fifths (43%) of us who turned 65 in 1990 or later will enter a nursing home at some point before we die, and 55% of those will reside in a nursing facility for at least one year. The probability of living in a nursing home increases dramatically with age, of course — rising from 17% for those aged 65 to 74 to 60% for people aged 85 to 94. And because women live longer than men, their risk of a nursing home stay over their lifetimes is higher (52% versus 33%) (NMFS, 1993).

So while only around 2.5 million people living in a residential long-term care facility may be at risk for abuse and neglect on any given day, far more of us may be at risk when we count those of us who will experience shorter-term stays in nursing homes.

The federal government has long been aware of the nursing home abuse-neglect problem. Beginning with the widely publicized late-1970s Congressional hearings on the mistreatment of the elderly, policy makers and practitioners have sought ways to protect golden-agers from abuse. Congressional passage of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1987 (OBRA 1987. Pub L. No. 100-203), in fact, implemented the most sweeping reforms to nursing home regulation since the passage of Medicaid and Medicare, addressing many areas of resident care and quality of life. The Act explicitly stated that “residents had the right to be free from verbal, sexual, physical, and mental abuse, including corporal punishment and involuntary seclusion,” (42 CFR Ch. IV (10-1-98 Edition) §483.13 (b) and limited the use of physical restraints and inappropriate use of psychotropic medications.

Yet a 2001 Congressional report found that over 30% of U.S. nursing homes (5,283 in 2003) had been cited for nearly 9,000 abuse violations that, in a two-year period, had the potential to cause harm to residents (U.S. House of Representatives, Waxman, 2001). Over one-third of those abuse violations were severe enough to cause actual harm to residents or place them in immediate jeopardy of death or serious injury. Nearly 10% of all nursing homes (1,601) were cited for abuse violations that caused actual harm, or worse, to residents.

The state inspection reports and citations reviewed describe many instances of appalling physical, sexual, and verbal abuse of residents. Some nursing homes were cited because a staff member committed acts of physical or sexual abuse against the residents under his or her care. Others were cited because they failed to protect vulnerable residents from violent residents who beat or sexually assaulted them. After all, isn’t it ultimately the staff’s responsibility to protect vulnerable residents from resident perpetrators of abuse?

It’s important to note that over 40% — more than 3,800 — of these abuse violations were discovered only after a formal complaint was filed. So, yes, we’re paying more attention to nursing home industry abuse and neglect now. But we still aren’t fully addressing the shameful problem that those responsible — and sometimes the neglected and abused themselves — want to conceal.

What Constitutes Nursing Home Abuse or Neglect?

While there’s no universal agreement as to exactly what constitutes neglect and abuse, definitions used by various government agencies are very similar. Abuse is generally considered to be the willful infliction of injury, unreasonable confinements, intimidation, or punishment that results in physical harm, pain, or mental anguish. Importantly, this includes isolation and the deprivation of goods or services that are necessary to attain or maintain a patient’s physical, mental, and psychosocial well-being. Abuse may take the form of physical abuse, sexual abuse, and emotional or psychological abuse.

For example, physical abuse includes: acts of violence such as striking (with or without an object), hitting, beating, pushing, shoving, shaking, slapping, kicking, pinching, burning, inappropriate use of drugs and physical restraints, force-feeding, or physical punishment of any kind.

Sexual abuse is defined as non-consensual sexual contact of any kind with another person, including sexual contact with any person incapable of giving consent. It includes, for example: unwanted touching, all types of sexual assault or battery, such as rape, sodomy, coerced nudity, and sexually explicit photographing.

Emotional or psychological abuse is defined as the infliction of anguish, pain, or distress through verbal or nonverbal acts. It includes, for example: verbal assaults, insults, threats, intimidation, humiliation, and harassment. In addition, treating an older person like an infant; isolating an elderly person from his/her family, friends, or regular activities; giving an older person the “silent treatment;” and enforced social isolation are examples of emotional/psychological abuse.

Neglect is defined as the refusal or failure to fulfill any part of a person’s obligations or duties to an elder. It may include the failure to provide goods and services necessary to avoid physical harm, mental anguish, or mental illness. Typically, this may involve a refusal or failure to provide an elderly person with life necessities such as food, water, clothing, shelter, personal hygiene, medicine, comfort, personal safety, and other essentials included in an implied or agreed-upon responsibility to an elder. Neglect may also include failure of a person who has fiduciary responsibilities to provide care for an elder (e.g., pay for necessary home care services), or the failure on the part of an in-home service provider to provide necessary care.

How Widespread is the Problem? A Look at the Numbers.

How is nursing home neglect and abuse reported? Generally, by residents and their family members, nursing home staff, healthcare practitioners, long-term care ombudsmen, (officials appointed to investigate individual complaints against nursing facilities), state investigators/surveyors, and other sources, such as nurse aide registries. Each of these sources of information confirm that the U.S. nursing home industry is allowing neglect and abuse to not only occur, but to occur with alarming frequency. In fact, the statistics are profoundly disturbing.

Reports By Patients and Family

In focus group interviews, surveys, and individual interviews conducted by Atlanta Ombudsmen, a startling 95% of Georgia nursing home residents interviewed reported that they had experienced neglect or witnessed other residents being neglected (Atlanta Long-Term Care Ombudsman Program, 2000). Appalling instances of abuse and neglect included: residents being left for hours or even days in clothing and bedding that was wet or soiled with feces; not being turned and positioned, causing pressure ulcers which, improperly treated, led to sepsis and death; ignoring residents’ call lights without providing assistance; residents scalded after being placed in too-hot tubs of water; not receiving enough help at mealtimes, thus, not getting enough to eat or drink, resulting, in some cases, in death from malnutrition and dehydration. This survey found that 44% of residents reported that they had been abused; 48% reported that they had been treated roughly; for example…

“They throw me like a sack of feed … [and] that leaves marks on my breast.”

— Georgia Nursing Home Resident

Thirty-eight percent (38%) of the residents reported that they had witnessed abuse of other residents, and 44% said they had seen other residents being treated roughly. For example, one resident reported:

“My roommate — they throw him in the bed. They handle him any kind of way. He can’t take up for himself.”

— Georgia Nursing Home Resident

Reports By Nursing Home Employees

“Oh, yeah. I’ve seen abuse. Things like rough handling, pinching, pulling too hard on a resident to make them do what you want. Slapping, that too. People get so tired, working mandatory overtime, short-staffed. It’s not an excuse, but it makes it so hard for them to respond right.”

— Certified Nursing Aide (CNA) from South Carolina (Hawes et al., 2003)

The results of studies that interview nursing home staff about committing or witnessing resident abuse and neglect suggest the problem may be even more widespread and severe than reports by residents and their families.

Highlights of key studies include:

- One 2010 study found that over 50% of nursing home staff actually admitted to mistreating (e.g. physical violence, mental abuse, neglect) older patients within a one-year period. Two thirds of those incidents involved neglect (Ben Natan & Lowenstein, 2010).

- A study of Certified Nursing Assistants (CNAs) found that 17% of CNAs had pushed, grabbed, or shoved a nursing home resident. Fifty-one percent yelled at a resident and 23% had insulted or sworn at a resident (Pillemer & Hudson, 1993).

- Investigative surveys of CNAs found that an overwhelming 81% of them had observed — and 40 percent had committed — at least one incident of psychological or emotional abuse during a 12-month period. Psychological abuse included yelling in anger (observed by 70%), insulting or swearing at a resident (observed by 50%), inappropriate isolation, threatening to hit or throw an object, or denying food or privileges (Pillemer & Moore, 1989).

- A 2000 CNA focus group study of 31 nursing facilities (MacDonald, 2000) supported the Pillemer and Moore findings, reporting widespread verbal abuse by staff:

- 58% of the CNAs observed instances of yelling at a resident in anger;

- 36% observed swearing at a resident;

- 11% witnessed staff threatening to hit or throw something at a resident.

- 25% of CNAs also witnessed rough treatment of residents, including staff isolating a resident beyond what was needed to manage his/her behavior; 21 percent witnessed restraint of a resident beyond what was necessary;

- 11 percent observed a resident being denied food as punishment.

- 21% percent witnessed a resident being pushed, grabbed, shoved, or pinched in anger;

- 12% witnessed staff slapping a resident;

- 7% witnessed a resident being kicked or hit with a fist;

- 3% saw staff throw something at a resident;

- 1% saw a resident being hit with an object.

In any other domestic environment in our society, we would comfortably classify such treatment of any child, any human — even our pets, for that matter — as abuse, behavior that warrants immediate intervention by law enforcement and perhaps a social services agency. Why, then, is it so hard to ensure that the same standards and remedies are applied to residents in nursing homes, many of whom are as utterly helpless to defend themselves as newborn babies?

Reporting By State Surveyors / Investigators

Nursing facilities that participate in the Medicare and/or Medicaid programs are subjected to an unannounced survey each year, conducted by state survey agencies, typically located in the state’s department of health. They follow a survey protocol developed, tested, and validated by the federal government. But this survey process has flaws, to be sure. For example, nursing home staff know approximately when these surveys will take place and can take measures in the interim to remedy or improve problems, if only temporarily, in order to avoid being cited for substandard care.

Nonetheless, this publicly-conducted survey is the only objective, independent assessment of a nursing facility’s quality of care, other than in instances when the investigators are called upon to report a specific complaint that has been made about a facility. So, while surveys are incapable of detecting all abuse and neglect, they can still shed additional light on the scope of the abuse-neglect problem. And, to be clear, the surveys have demonstrated that U.S. nursing homes have failed time and again to even meet the minimum regulatory standards required to ensure adequate care to the patients.

For example, a U.S. House of Representatives Report found that 1 in 3 nursing homes were cited for violations of federal standards from 1999-2001 that had the potential to cause harm or had caused actual harm. Nearly 1 of 10 nursing homes had violations that caused residents harm, serious injury, or placed them in jeopardy of death (U.S. House of Representatives, Waxman, 2001). And we know that elder mistreatment is, in fact, strongly associated with increased mortality rates (Gibbs, 2004).

A 2001 U.S. House of Representatives Report included these key statistics on abuse violations over a two-year study period:

- Over 30% of U.S. nursing homes (5,283) were cited for an abuse violation.

- Overall, 1,327 nursing homes were cited for more than one abuse violation. A total of 305 homes were cited for three or more abuse violations, and 192 nursing homes were cited for five or more abuse violations.

- Over 2,500 of the abuse violations were serious enough to cause actual harm to residents or to place residents in immediate jeopardy of death or serious injury. Nearly 10% of U.S. nursing homes (1,601) were cited for abuse violations that caused actual harm to residents or worse.

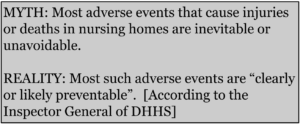

More recently, a 2014 report by the Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services (Levinson, OIG, 2014) confirmed a shocking number of preventable injuries and death due to neglect, finding that one third-of nursing home residents in a Medicare-nursing home stay suffered an adverse event or other harm in the month of August 2011, and that most of the events were “clearly or likely preventable.”

Key highlights of this 2014 OIG report include:

- Physician reviewers found that 59% of the adverse events and incidents of temporary harm were preventable, attributing much of the preventable harm to “substandard treatment, inadequate resident monitoring, and failure or delay of necessary care.” Preventable events included: 66% of medication events; 57% of resident care events; 52% of infection events.

- Few staffing deficiencies were cited and, in many cases, even the most serious deficiencies — those identified as causing residents “immediate jeopardy” — were never sanctioned in any way.

- In a one-month period, an estimated 1.5 percent of Medicare nursing home residents (1,538 people) experienced adverse events that contributed to their deaths. For most of them, death was “likely not an expected outcome.”

- These adverse events were related to:

- Medication (37%)

- Resident Care (37%)

- Infection (26%), including aspiration pneumonia and other respiratory infections (10%)

- Temporary events under the same three categories included:

- Medication (43%)

- Resident Care (40%), including pressure ulcers (19%)

- Infections (17%)

In 2014, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) also reported deficiencies (Annual Nursing Home Data Compendium, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, (CMS, 2015):

- U.S. nursing homes were cited for 5.7 health deficiencies each, on average, per state, totaling 89,148 citations (i.e., 5.7 x 15,640).

- 95.1% of the Health Deficiencies cited had potential for “more than minimal harm” involved “actual harm,” or involved “immediate jeopardy to resident health or safety.”

The Bottom Line

So what’s the take-away? The bottom line is two-fold…

First, patients, families, nursing home employees, and state surveyors all report that nursing home neglect and abuse is a decades-old problem that continues to this day with shocking frequency and tragic results. As alarming as the statistics are, they actually reflect only a portion of the problem for reasons that will be discussed in more detail later.

To add insult to injury, over 50% of the residents who experienced harm were hospitalized for treatment, costing Medicare (thus, U.S. taxpayers) an estimated $208 million in the month of August 2011 alone. Thus, not so indirectly, we are all forced to help subsidize the financial burden of the nursing home industry’s neglect and abuse. And this cost is on top of the Medicare and Medicaid payments that we, as taxpayers, pay the nursing home industry in exchange for promising to properly care for their patients in the first place.

But second, and importantly, there is hope. Despite the staggering enormity of the abuse-neglect problem, there are steps that you can take to hold bad nursing homes accountable. First, you can make sure you are informed of the rights each nursing home patient has under federal law. You can also engage a long-term care ombudsman to help you resolve concerns you have about quality of care problems in a nursing home facility. If that does not resolve the problem, you can file a complaint against the nursing home with the government entity responsible for investigating complaints of nursing home abuse or neglect. Finally, you can consult with an experienced lawyer who is familiar with how to hold bad nursing homes accountable. When bad nursing homes are held accountable for providing substandard care, it sends a message to other nursing homes that the community will not tolerate nursing home neglect or abuse.

Unfortunately, the struggle against this long-standing epidemic of nursing home abuse and neglect continues. Nursing home industry forces are powerful because of the enormous financial profits they garner. However, there are tools at our disposal to help fight back on behalf of patients who are harmed. Only by holding bad nursing homes accountable in a meaningful way can we expect them to take affirmative steps to fix their broken ways, and to help ensure that the patients entrusted to them are cared for properly.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

Q: What is nursing home neglect?

A: Neglect is defined as the refusal or failure to fulfill any part of a person’s obligations or duties to an elder. It may include the failure to provide goods and services necessary to avoid physical harm, mental anguish, or mental illness. Typically, this may involve a refusal or failure to provide an elderly person with life necessities such as food, water, clothing, shelter, personal hygiene, medicine, comfort, personal safety, and other essentials included in an implied or agreed-upon responsibility to an elder.

Q: What is nursing home abuse?

A: Abuse is generally considered to be the willful infliction of injury, unreasonable confinements, intimidation, or punishment that results in physical harm, pain, or mental anguish. Importantly, this includes isolation and the deprivation of goods or services that are necessary to attain or maintain a patient’s physical, mental, and psychosocial well-being. Abuse may take the form of physical abuse, sexual abuse, and emotional or psychological abuse.

Q: How can I report nursing home abuse or neglect?

A: If you suspect a resident is being neglected or abused, you should contact your local long-term care ombudsman. You can also file a complaint with your state’s health department, which is responsible for investigating complaints of nursing home abuse or neglect. You may also benefit from consulting with an experienced attorney who is familiar with how to hold bad nursing homes accountable.

REFERENCES

Annual Nursing Home Data Compendium, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS), 2015.

Atlanta Long-Term Care Ombudsman Program. (2000) The Silenced Voice Speaks Out: A Study of Abuse and Neglect of Nursing Home Residents.” Atlanta, GA: Atlanta Legal Aide Society, and Washington, DC: National Citizens Coalition for Nursing Home Reform.

Ben Natan, M., & Lowenstein, A. (2010). Study of factors that affect abuse of older people in nursing homes. Nursing Management, 17(8), 20-24.

Broyles, K. (2000). The silenced voice speaks out: A study of abuse and neglect of nursing home residents. Atlanta, GA: A report from the Atlanta Long Term Care Ombudsman Program and Atlanta Legal Aide Society to the National Citizens Coalition for Nursing Home Reform.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (1993) National Mortality Followback Survey With Death Certificate, Proxy Respondent, and Medical Examiner/Coroner Abstract Data File Description. 1993.

Gibbs, Lisa M., MD (2004) Annals of Long-Term Care: Clinical Care and Aging;12[4]:30-35).

Hawes C. Elder (2003) Abuse in Residential Long-Term Care Settings: What Is Known and What Information Is Needed? In: National Research Council (US) Panel to Review Risk and Prevalence of Elder Abuse and Neglect; Bonnie RJ, Wallace RB, editors. Elder Mistreatment: Abuse, Neglect, and Exploitation in an Aging America. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US). 14.

Levinson, Office of Inspector General, Adverse Events in Skilled Nursing Facilities: National Incidence Among Medicare Beneficiaries, OEI-06-11-00370 (Feb. 2014).

MacDonald P. Make a Difference: Abuse/neglect Pilot Project. Danvers, MA: North Shore Elder Services; 2000. Project report to the National Citizens’ Coalition for Nursing Home Reform, Washington, DC.

Pillemer K, Hudson B .(1993) A model abuse prevention program for nursing assistants. The Gerontologist. 1993;33:128–131.

Pillemer, K. & Moore, D. (1989). Abuse of patients in nursing homes: findings from a survey of staff. Gerontologist, 29(3), 314-320.

Jeff Powless is an attorney and the author of the 2017 book, Abuses and Excuses: How To Hold Bad Nursing Homes Accountable. Abuses and Excuses breaks new ground in helping patients and families hold bad nursing homes accountable, sharing a wealth of insider strategies and insights. It’s an eye-opening account of corporate greed, acts of neglect and abuse, an insidious industry culture of cover-up, and the actual harm that inevitably befalls vulnerable nursing home patients all across the country with shocking frequency.

Jeff Powless is an attorney and the author of the 2017 book, Abuses and Excuses: How To Hold Bad Nursing Homes Accountable. Abuses and Excuses breaks new ground in helping patients and families hold bad nursing homes accountable, sharing a wealth of insider strategies and insights. It’s an eye-opening account of corporate greed, acts of neglect and abuse, an insidious industry culture of cover-up, and the actual harm that inevitably befalls vulnerable nursing home patients all across the country with shocking frequency.